Adele Harty

SDSU Extension Cow/Calf Field SpecialistAdditional Authors: Patrick Wagner

Written collaboratively by Adele Harty and Patrick Wagner.

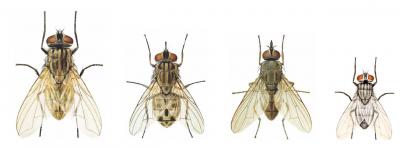

Along with being irritants to livestock, horn flies, face flies and stable flies are economically important to producers due to their negative impacts on milk production and calf weaning weights. In addition, they can affect grazing distribution and transmit eye diseases, such as pinkeye and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR). It is difficult to predict what fly levels will be like for any given year, but hot, dry weather can speed up development and usually results in high numbers. It is important to identify (Figure 1) and understand life cycles of external pests affecting livestock in order to choose the most-effective control options.

Horn Flies

Horn flies are one of the most common and economically important ectoparasites of pastured cattle. Economic losses are estimated at more than $1 billion annually in the United States. This loss is a result of skin irritation, blood loss, decreased grazing efficiency, reduced weight gains and decreased milk production. Research in Nebraska found that calf weaning weights were 10–20 pounds (lbs.) heavier when flies were controlled on the cows.

Horn flies are about 1/2 to 1/3 the size of the common house fly, or approximately 3/16 of an inch long. They are commonly found on the backs, sides and polls of cattle. During the heat of the day, horn flies will migrate to the belly. As adults, they spend most of their time on cattle, piercing the skin of host animals to suck blood. Both male and female horn flies may take between 30 and 40 blood meals per day. After mating, the adult females deposit eggs in fresh manure and the eggs typically hatch within one week. The total life cycle of the horn fly is between 10 and 20 days, depending on weather conditions.

MANAGEMENT

The economic injury level (EIL) for horn flies is 200 flies per animal. At this point, the economic impact of the pest equals treatment costs, and a treatment plan should be started. Multiple insecticide options are available to manage horn flies, including dust bags, backrubbers (oilers), feed additives, sprays, pour-ons and insecticidal ear tags.

Dust bags or oilers may be either forced-use (placed in an area that animals must pass through) or free choice. However, if they are not in a forced use area, expect 35–50% less control. In a forced used setting, they offer good control, but require time checking and repairing bags.

Feed additives, such as oral larvicides and insect growth regulators (IGRs), pass through the animal’s digestive system and prevent horn fly larvae from developing in the manure. While these additives are effective in reducing the number of larvae, this does not necessarily correlate to a reduction in the number of adults, since flies will migrate to and from neighboring herds. Also, it is difficult to control intake of these feed additives, and some animals may not eat enough of the feed additive for the insecticide to be effective.

Sprays and pour-ons require applications every two-to-three weeks, which may not be feasible for some producers’ summer grazing situations. Another option is the VetGun, which is a device similar to a paint ball gun that can be used to apply an individual capsule of insecticide to an animal. This method can provide horn fly control for 21–35 days, but it has limitations for large herds and retreatments.

Insecticidal ear tags contain an insecticide that moves from the surface of the tag to the coat of the animal. They are easy to apply and can be effective; however, there is a history of horn fly resistance to the active ingredients used in some tags. Products vary, but some general guidelines are listed below.

- Tag animals as late as possible to ensure maximum effectiveness when horn flies are present. Do not tag earlier than June 1.

- Tag mature cows and weaned calves. There is no need to tag nursing calves, as horn flies typically do not bother them.

- Remove used tags at the end of the season. This will help reduce the incidence of resistance.

- Use high-quality tags. Inexpensive tags are generally not as effective.

It is recommended to rotate to tags with a different active ingredient to impede resistance development. Do not apply insecticides from the same Mode of Action (MOA) groups repeatedly. Instead, rotate between MOA groups each year or even during the fly season. Mode of action groups include organophosphates (Group 1B), pyrethroids and pyrethrins (Group 3), avermectins and milbemycins (Group 6), juvenile hormone analogues (Group 7A) and benzoylureas – chitin inhibitors (Group 15).

Face Flies

Face flies resemble house flies, but they are slightly larger and darker. They are non-biting flies that cluster around animals’ eyes, mouth and muzzle to feed on secretions. Females lay eggs in fresh manure, with the complete life cycle taking around 21 days. They are usually most numerous in late July and August in pastures that have a lot of shaded areas and waterways, areas with abundant rainfall and irrigated pastures. Face flies can cause irritation to eye tissues, which can predispose animals to disease transmission. Pinkeye is one such disease, and management of face fly populations is essential in preventing outbreaks. If pinkeye is a recurring problem, it is a good idea for producers to visit with their veterinarian about vaccine options.

MANAGEMENT

Managing face flies can be difficult because of their feeding locations on animals and the fact that they do not spend the majority of their time on animals. Effective control may require more than one method of treatment, including the use of insecticidal ear tags, dust bags and sprays. In contrast to horn flies, both cows and calves must be treated in order to reduce face fly populations.

Stable Flies

Stable flies are the size of a house fly, but darker in color. These are blood-feeding flies that mainly feed on the front legs. The most-common sites for development of stable flies are feedlots or dairies, as larvae develop in decaying organic matter, such as wet hay. However, they can also be found on pastures, particularly around winter hay feeding sites. Cattle often react to stable flies by bunching, stomping their legs or standing in water. This can disrupt grazing patterns, and Nebraska studies indicate reductions in weight gains from 0.2–0.4 pounds per day for grazing steers.

MANAGEMENT

It can be difficult to get adequate control with insecticides, since stable flies mainly congregate around animals’ legs. Sprays are usually the best option for stable fly control and require weekly applications to manage populations. Mist blower sprayers can be used for this purpose; however, initial costs may be high. One of the best ways to eliminate stable flies is to remove sources of organic matter that create breeding grounds. Cleaning areas where cattle were fed during the winter and drying down manure by spreading it or dragging fields will help reduce fly populations.

A successful fly control program requires proper identification of the pest(s), determining the best control method, and following label directions on the product to get optimum control and decrease the chance of resistance. A listing of products available for control of insect pests can be found in the Nebraska Management Guide for Insect Pests of Livestock and Horses.